High Output Management: 3 Key Concepts From The Book

Andy Grove’s High Output Management (1983) influenced a generation of leaders in Silicon Valley who could relate to Grove’s systems-and-processes engineering approach to management.

The result is a unique book that treats the idea of “management” as a hard skill — focused on outputs, objectives and results.

In this summary, we’ll go over 3 of my favorite concepts from the book:

#1 — Great managers understand the value of Leverage

According to Grove, your job as a manager is not just to “manage people” … but to maximize output from your team and the ones around you:

A manager’s output = The output of his organization + The output of the neighboring organizations under his influence

This is a recognition that managers are multipliers for performance — great ones positively amplify performance, while poor managers dampen performance (or create negative performance). I’m sure we’ve all seen a team where the manager is so bad that they not only drag down their own team’s performance, but the teams around them as well.

Great managers are multipliers because they understand the importance of high-leverage activities.

Every activity you do as a manager has leverage; great managers correctly identify which activities have the highest leverage and give those appropriate time and attention.

Here’s how I think about it.

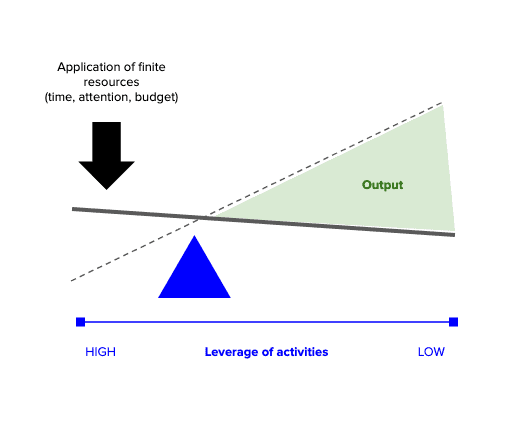

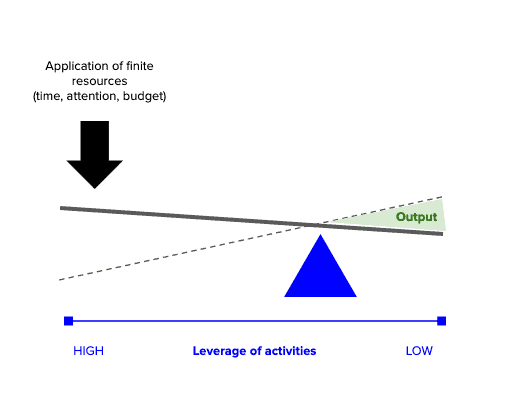

As a manager, you have control over (1) how you apply your finite resources and (2) the leverage of activities you choose. Therefore, here’s what “high output management” could look like:

And conversely, “low output management”

High Leverage Activities

High Leverage activities are those that have lasting impact at scale — they affect lots of people, they affect alignment, they shape future behavior. Examples:

- Recruiting, onboarding and training. This is one of the highest leverage activities you can influence as a manager, and it’s incredibly important to get it right.

- Rewarding performance. Choosing who you reward and how you reward them is another high leverage activity, because it sends signals throughout the org about what is model behavior and what isn’t. For example, if you promote someone who is a great team player and liked by everyone, but isn’t a high performer – you are sending a signal that it’s okay to underperform as long as you get along with everyone.

- Cross-team communications. Company meetings and cross-team working groups – especially with other managers and executives – are high leverage activities, since they can potentially influence the activities of people far beyond a manager’s direct reports. Poor managers either under-value these activities (eg. showing up unprepared, botching an important presentation) or totally neglect their importance, which leads to them and their team operating in a silo.

A personal caveat: while getting the above right is extremely important, nailing high leverage activities alone is not going to guarantee meaningful output. There’s also a meta-layer of strategy and making sure you and your team are working on the right things. That’s beyond the scope of this post, but something important to consider when trying to maximize your own output.

#2 — Manage people according to Task-relevant maturity (or, why micromanagement is not the enemy)

Grove is agnostic about “management styles.” True to his engineering background, he just wants the right tool for the right problem.

To him, there is no “good” or “bad” management style. Only effective and ineffective ones. And that brings us to the concept of task-relevant maturity (TRM).

Task Relevant Maturity

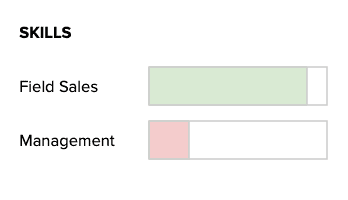

Grove gives an example in the book where a top field salesman at Intel was promoted to head office to become a manager, but then struggled terribly.

His explanation is simple:

The salesman got promoted because of his high TRM in sales, but in his new position as a manager, he had low TRM. Therefore – without the proper coaching from his boss, it was almost a foregone conclusion that that he would underperform in his new role.

What should his boss have done, knowing this?

Micromanage the salesman!

Contrary to popular belief, micromanagement is not a dirty word.

A whole generation of workers has been brainwashed to think that ALL micromanagement is bad.

Here are 2 pictures showing where micromanagement is totally appropriate:

Defaulting to “macromanagement” just because people vilify micromanagement is poor management. One is not better than the other: it depends on the level of Task Relevant Maturity.

If you have someone on your team with low TRM in an important task, it is your duty to micromanage them until they exhibit an appropriate level of TRM.

Just because someone is a high performer at X does not automatically mean they’ll be good at Y. Just because someone came from Big_Company_X does not mean they’ll thrive in your company. Jason Lemkin talks about this (“hire for stage fit, not pedigree.”)

#3 — You need to manage information Like a Boss

“Information is the basis of all managerial output, which is why I spend so much time gathering it”

If we accept the ideas that managers are multipliers, and that accurate calibration is a key part of their performance … then it becomes obvious managers cannot realize those two things unless they are plugged into, and can direct, the flow of information in the company.

Here are two ways great managers do that:

Running 1 on 1 Meetings

To those who work in tech, or any industry where 1 on 1 meetings are built into the operating system of the company, we have Andy Grove to thank!

Whenever I’m talking to a friend who’s ranting about their job, 99% of the time it’s because of some information gaps between manager and employee. Things that could have easily been solved just by running regular catchups between a manager and her direct reports.

But 1-1s are not just about “catching up.”

As a manager, it’s important to let your team feel like their 1-1 meeting is their space to talk about anything and raise things that are bothering them. But don’t forget that 1-1s, in addition to the building psychological safety and trust, have a purpose for the manager:

- 1-1s are there to increase leverage. The “job” of the 1-1 is to help you increase your overall output. There are several ways you can use 1-1 time to do this (building rapport, psych safety, project feedback, etc) but don’t lose sight of the overall objective.

- Calibrate on TRM. Have you given your reports something too big for them to chew on? Too small? Do they need course correction? 1-1s are the avenue for you align on these topics with your reports.

- Provide coaching. In addition to project-specific coaching, and aligning on TRM, 1-1s are also a mechanism for providing longer term performance feedback to improve their output.

A manager should dedicate half a day a week per subordinate … and top out at 8 direct reports.

1-1s can and should take up a lot of time and energy – but Grove thinks it’s worth it. His reasoning is that as a manager, you get maximum leverage through your direct reports, so it is logical that improving their output is very high ROI activity. But he knows this is time consuming, so provides guardrails on how much time managers need for each report.

Allowing Information To Flow Freely

Grove is a believer in transparency – not just openness for the sakes of openness – but because transparency can help you make the best decisions possible.

Good leaders promote the flow of ideas, facts, experiences and perspectives.

This sounds obvious, and very few would disagree with this statement, unless your leadership style is by ruling with an iron fist. But how do you actually do that?

Here’s a few examples from the book about what it looks like in practice:

- For each decision, identify who the actual decision maker is. Otherwise, you’ll run into something Grove calls “peer group syndrome” – I’m sure we’ve all been in a group where everyone contributes their ideas but it’s not clear how to move forward, or it’s unclear how to resolve conflicting views. The fix for this is by pausing before the project starts to define who should own the decision. (side note: it’s not from the book, but the DARCI model is another solve for this problem)

- For big decisions, first create a framework for how the decision will be made. Grove gives an example of his team at Intel deciding where to build a manufacturing plant – many stakeholders, lots of tough questions, lots of ambiguity, and lots at stake. The only way they made a high-quality decision was by having a transparent decision making process that was set upfront.

- Avoid vetos. A veto, no matter how rational, if unexpected or opaque, creates the appearance of unfairness and politicking. Sometimes, vetos are unavoidable, but be conscious that they incur a cost of undermining the integrity of the decision making process over the long term.

- Build a racetrack. Grove uses a few sports analogies in the book – and he’s a fan of “racetracks” because they set clear expectations, where it’s obvious what winning and losing looks like. For example, if you have two similar teams whose functions are similar (eg. different teams in Sales), it’s possible to get better performance from them simply by comparing them to one another – either natural competitiveness will kick in, or they’ll share best practices with each other.

High Output Management as a field manual

High Output Management is a celebration of the middle manager. Unlike most management books, it really really gets into the weeds of management, and can get really prescriptive about how to do things. This is really refreshing for those who want a very high fidelity, precise view of what “great management” can look like.

It’s one of my favorite books, and easily earns its place on my list of best books to become a better marketer.

Read more detailed summaries of this book here: