How Brands Grow: A Short Summary

Byron Sharp’s How Brands Grow: What Marketers Don’t Know was an eye opener for me, because he was right — there was a lot of stuff that I, as a marketer, did not know.

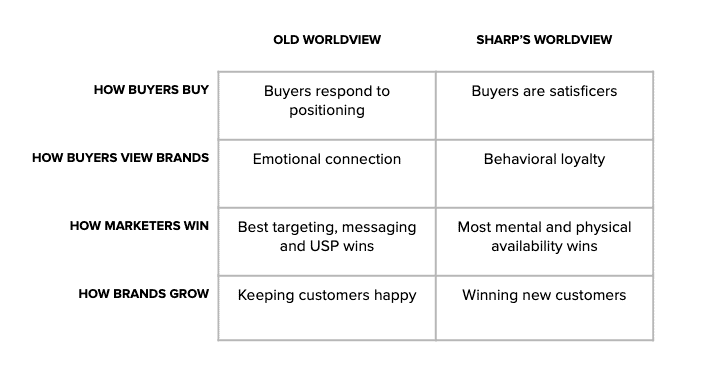

Sharp is basically like: “Hey marketers, your model of how marketing works is all wrong. You’ve been trained that good marketing and brand growth comes from emphasizing emotions, positioning and loyalty. But it doesn’t work like that.”

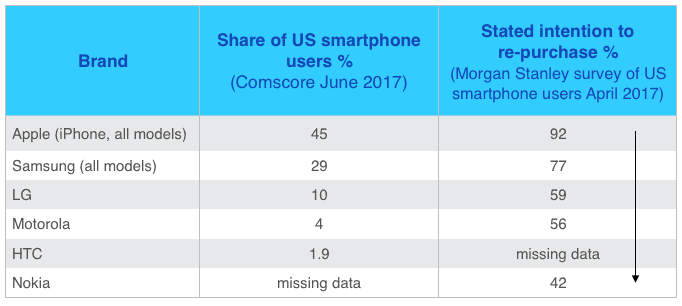

Here’s my one-table summary of How Brands Grow:

And here’s my one sentence summary of How Brands Grow:

Brands grow by focusing on new customer acquisition, driven by increasing mental and physical availability, resulting in behaviorally loyal buyers.

Let’s go through these one by one.

Brands grow because they focus on getting new customers

In Sharp’s view, marketers are incorrectly trained to think that the ideal outcome of marketing and brand growth is the hyperloyal buyer, the one who tattoos your logo on their arm and evangelizes your brand to their friends.

This is captured in versions of this statement that we’ve all heard:

Acquiring new customers is X times more expensive than keeping your current customers.

The implication is that growth comes from retention and driving repurchase from existing customers.

Sharp rejects this sentiment for a few several reasons: (1) the study on which it was based has dubious methodology and (2) it contradicts how market dynamics work. It’s one of those proverbs that have kind of crept into mainstream marketing, and is unquestioned because it has a nice “truthiness” to it.

Instead, Sharp says that your brand’s growth is going to come from light buyers — or nonconsumers.

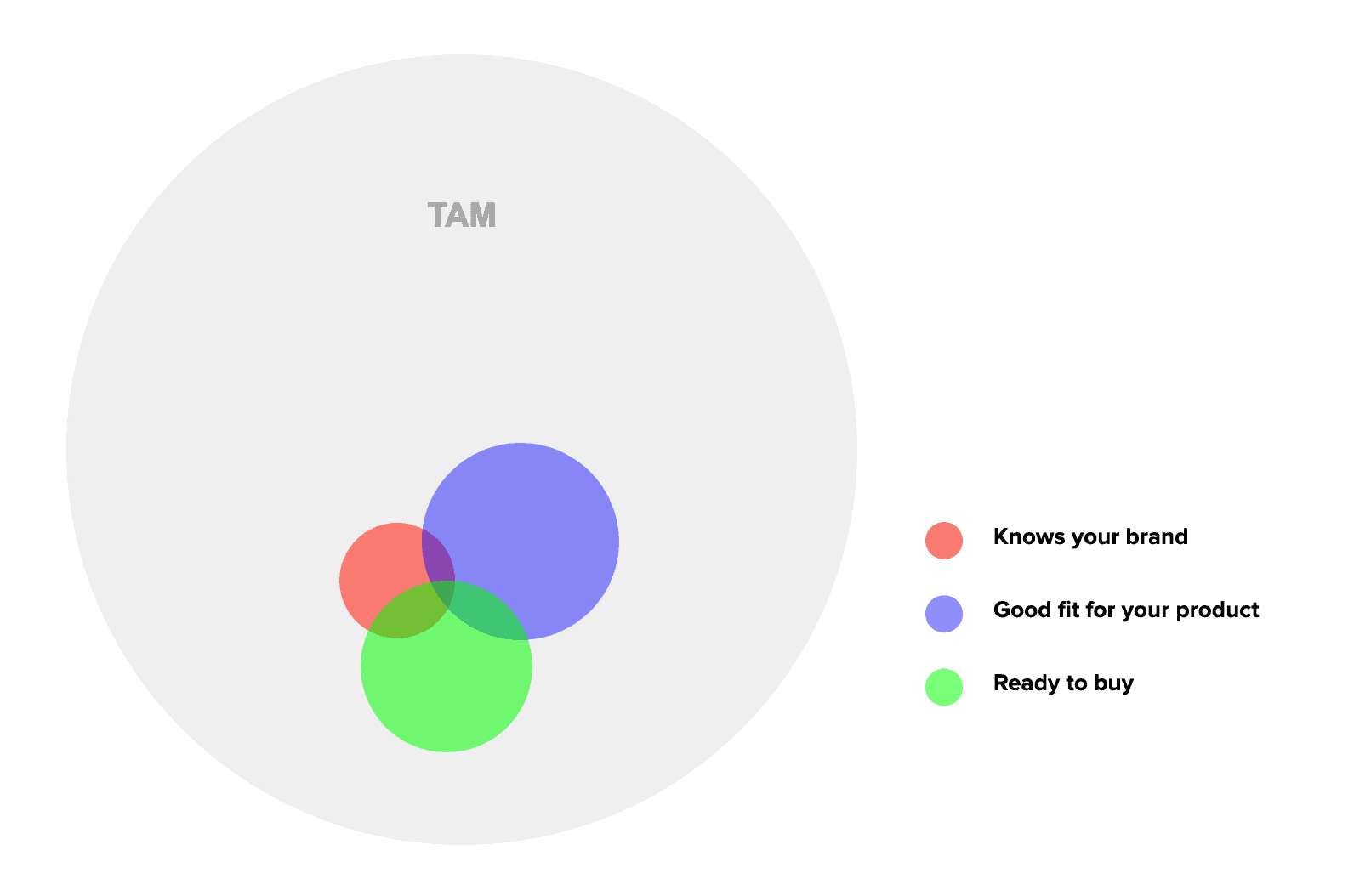

This isn’t from the book, but here’s a diagram I made to try to better understand this:

If you just focus on preventing churn or increasing repurchase rates, you’re only working within the red bubble — there’s only so much growth available there.

If your goal is to grow a brand and getting more business, increasing the size of the “knows your brand” bubble is the best use of your time and resources.

One big reason why this happens is because you compete with things outside of just the other brands in your category. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings has a great way of thinking about this when asked about Disney+ and competition. He understands that consumers will probably subscribe to multiple services, or hop back and forth between services, but he views his real opportunity as flipping “light buyers” (skip to 1:50)

What this all means for marketers:

- Go after light buyers and non-consumers. You should always be increasing the number of potential buyers who have heard of you. Your job is to show up in as many buying windows and consideration sets as possible. Don’t take your eyes off increasing the size of the red bubble.

- Challenge the need for loyalty or rewards programs. Your heavy buyers are going to buy from you anyway, so you’re just subsidizing purchases that would’ve happened regardless. Unless you have a higher level strategic reason for doing these programs, your resources are likely better spent on getting new customers.

Brands grow because they have more mental and physical availability

Sharp spends a lot of time reminding you that people are cognitive misers, and we should view buying behavior through that lens.

“Traditional” marketing places a lot of weight on positioning, segmentation, and messaging — which Sharp thinks are overrated.

People are satisficers. We take mental shortcuts. We are prefer things that have high cognitive ease.

Therefore, Marketers should focus less on differentiation — obsessing over the perfect articulation of your USP — and more on distinctiveness: being unique and easy to recall.

Sharp emphasizes the importance of having high mental availability and physical availability. I had a tough time really internalizing what this means, but here’s my shot at what each of these mean:

Mental availability refers to the amount of “brain space” a brand takes up in your head. The book primarily has FMCG brands examples, so Sharp describes this in terms of advertising campaigns and packaging. But it could also mean SEO footprint, content marketing, podcast downloads. More brain space = easier to recall during a buying situation.

Physical availability refers to a brand’s presence during a buying situation. Examples of low physical availability: Being out of stock at the grocery store. Your website crashing on Black Friday. Not being on Amazon when your buyers are expecting you to be there.

See also: my summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow

What this means for you as a marketer:

- Constant advertising, not bursts. Remember, your job is to be easy to recall, and it’s easy to be recalled when you’re always reminding people that you exist. This is the reason why Coke, Nike and Apple advertise even though we all know who they are. Can’t afford to be everywhere all the time? Prioritize the target buyers that should be keeping you top of mind, and spend your budget accordingly.

- Creative, distinct campaigns that cut through. People are cognitive misers; to get noticed, you have to make sure that you get their attention. You don’t have to be super funny or super clever, or even super likable – the point is to be distinct and stand out.

- Branding matters: be recognizable. The worst thing you can do as a marketer is run an award-winning campaign … but people don’t know who made the ads. Each touchpoint should reinforce a previous touchpoint, so look and feel and tone of voice are important.

Brands grow because of behaviorally loyal buyers

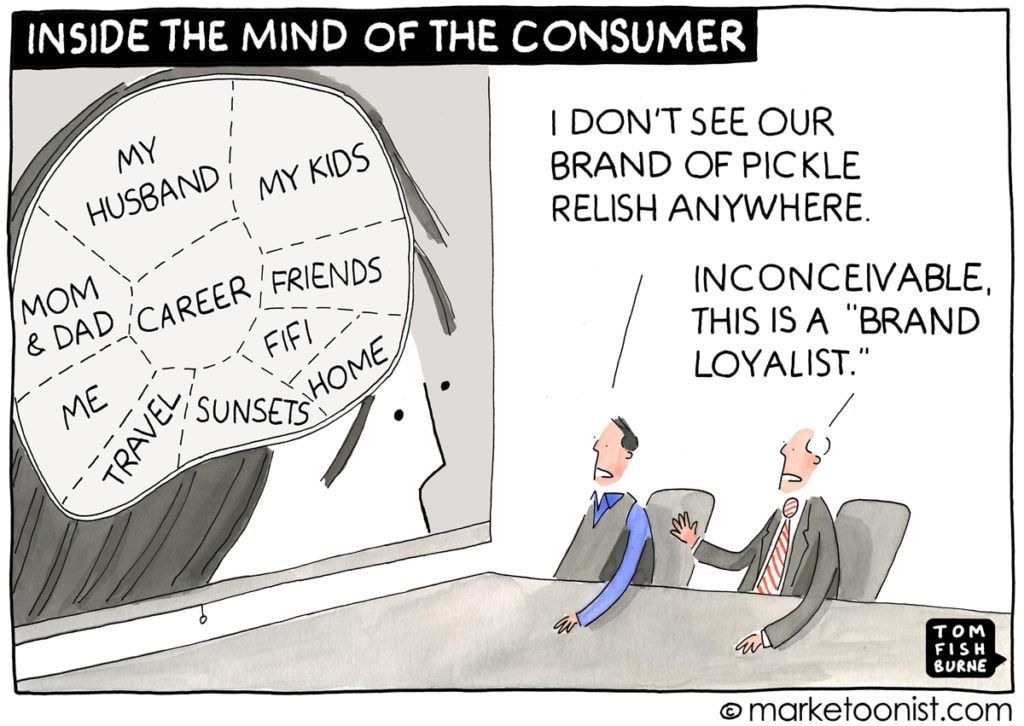

Sharp “debunks” some marketing mythology — like the idea that buyers are emotionally loyal (think: Harley Davidson buyers getting the brand tattoos.)

While that may be true in some outlier cases, the vast majority of “loyal” buyer behavior looks something like this:

I need to buy detergent.

Okay, I’ll just get the same brand I always get.

I’ve been buying it for years and nothing has gone wrong, so I’ll just buy it again.

This is consistent with the view that people are satisficers, we use heuristics, we hate thinking if we don’t have to. If something is good enough, even if it’s not the objectively best solution for our needs, we’ll go forward with it, because we’d rather think about other stuff.

A huge part of the book is Sharp’s exploration of the Double Jeopardy Law: which says that loyalty is a function of your market share. It’s called Double Jeopardy because brands with high market share have the most loyalty, which then means that brands with low market share also have the least loyalty.

What does this mean for you as a marketer?

- Don’t spend too much time making emotional appeals, or trying to build emotional connections. People just don’t work that way. You can do it, but don’t expect it to radically alter purchase behavior.

- Lower the friction of buying from you. People default to the path of least resistance. Make it easy for people self-serve. Have better customer service. Reduce response times when someone has a question.

A few closing notes on advertising and marketing

If you’re reading this because you’re thinking of buying this book — you should just go ahead and buy it. It’s a dense read full of insight.

Here are a few more ideas that stuck with me, but I couldn’t find a place for in the above summary:

- Advertising as a weak force. The wrong mental model of advertising is that it can produce changes in buyer behavior; the right campaign, the right ad, delivered at the perfect time with the perfect message, can get someone to totally stop what they’re doing and get you to buy. A better mental model is to think of advertising as a weak force, where each exposure nudges up someone’s propensity to buy just a little bit. This explains:

- Why advertising is so hard to measure. If you believe that advertising is a weak force, then it then follows that sometimes people might not even realize they’ve seen an ad, or they’ll vaguely recall info about a product but not sure where they heard it from (“how did you her about brand X?” … “I don’t know, I heard about it somewhere.”) And the time horizon of advertising is notoriously difficult to nail down, and rarely captures the full scope of impact. Imagine that your likelihood of buying brand X is 1/500. Seeing an ad might have nudged that to 2/500 – infinitesimal to you – but viewed from the brand’s POV, they’ve just doubled their sales.

- Sharp’s “Penetration” brand growth model should be used with a “Targeting” sales growth model. This video from Mark Ritson explains it better, you should just watch it.

Read this next: The Best Marketing Books To Become a Better Marketer