Perfect Marketing Can Still Fail

I feel a little bad for the marketing team behind the Game of Thrones prequel.

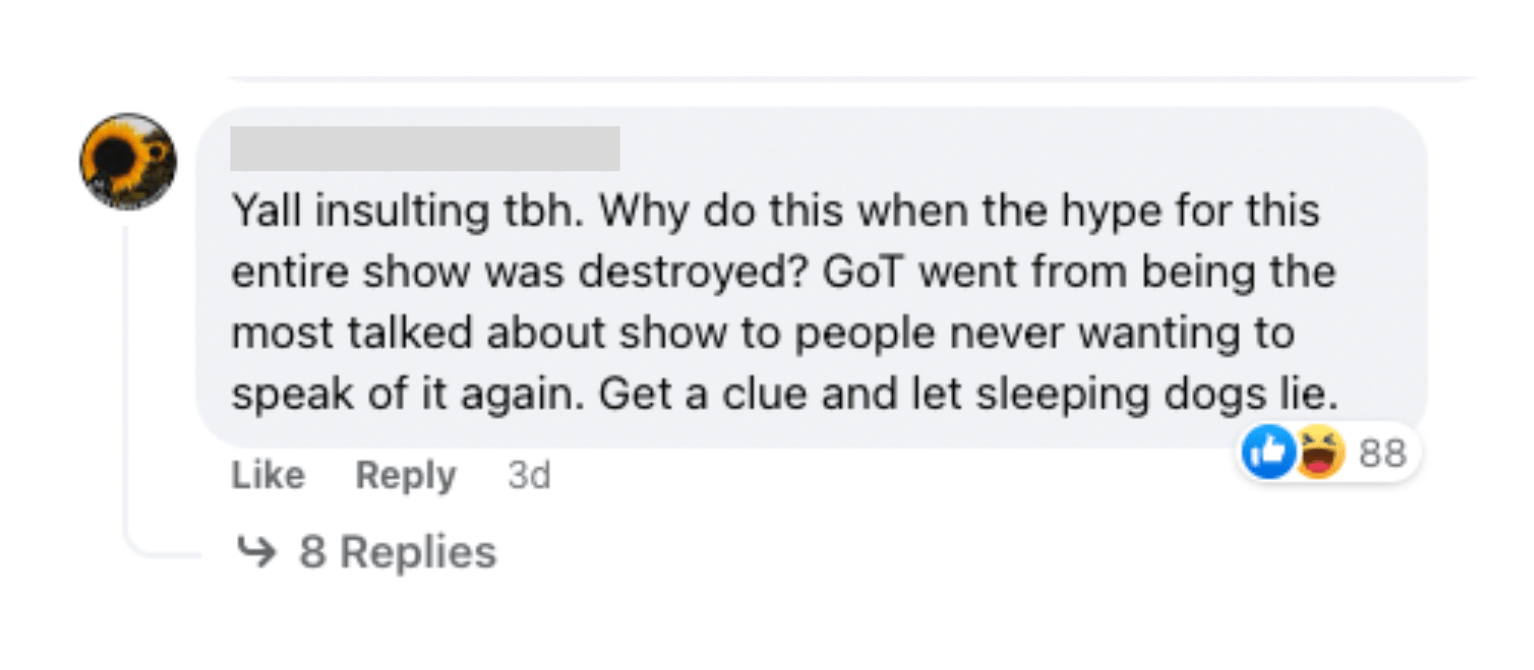

At time of writing, it's due to come out in a few months. Every time the HBO team posts something on social media, they usually get a deluge of comments like this:

Most of such comments are not about the trailer itself being bad or the promo looking cheap or poor quality. In fact, if you look at the advertising for the show – you'll find that it's pretty top-notch.

Is all this online hate going to translate into lower viewership?

Let's put it this way: I have a really hard time seeing how this show is going to garner a meaningful audience, especially with so many GoT fans still feeling burned. The controversial final season of the show transformed what was probably a 0.9 affinity rating to something to like 0.1. There's also way more entertainment choices today than in 2011, when the first run debuted.

This takes me to one of the most heartbreaking realities of marketing:

Sometimes, you can have a perfect strategy, with the perfect amount of budget, and with the perfect execution. And the campaign can still fail.

I learned this when I spent some time working in video games.

In gaming, everyone is obsessed about retention curves. It's a hyper-competitive industry where the fate of a game is determined in the first 60 days of its launch. Sometimes, if it's really bad, you'll know in the first 7 days.

I remember doing marketing and community engagement for one particular game that was loved by a small, passionate set of gamers, but didn't have remarkable retention curves. I spent some time coming up with a marketing plan to try to influence the retention curves, then presented it to a few of my veteran teammates.

They saw the plan and just ... kind of chuckled. My sweet summer child. How could you not know that this is pointless? The performance was already baked, there's no point in trying, the die was cast, the best thing you could do is to prepare for the next game and hope that one does better than this one.

I was disappointed, but after seeing multiple game launches, I realized they were right. I also realized that this applies not just to products, but to companies.

There are moments when I've been invited to speak at a panel, and I can feel that my answers annoy the audience. Like, I'll get asked sometimes how I'd solve problem X, and after some back-and-forth with the questioner to get a better read on the situation, I say something like:

"My advice to you is that you're going to be wasting a lot of your effort, because your product and company are not setting you up for success. You should actually find another job."

This is not the answer they were seeking, but the answer I believed they needed to hear. People don't like this and find it annoying. They don't understand that changing a retention curve is a "whole company" exercise involving major strategic and cultural changes. A bad system beats a good person every time.

This is one of the reasons I repeatedly argue that one of the most important skills you'll ever have as a marketer is not SEO or managing people or PR strategy or whatnot. It's the skill of how to evaluate companies to join in the first place.

I'll leave you with this quote from someone who has seen many more game, product and company launches than I ever will:

Should you find yourself in a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.

- Warren Buffett