Thinking Fast and Slow Summary: 7 Important Concepts From the Book

Writing a summary for Thinking, Fast and Slow was not easy.

Don’t get me wrong. Kahneman wrote a fantastic book that will help you improve your thinking and help you spot cognitive errors. I found it tough (worthwhile, but tough — like eating a salad you know you need to finish) to get through because it comes in at a very dense 500 pages.

If you’re reading this, it’s possible that you’re halfway through the book and just want someone to give you the gist of it. Or maybe you’re thinking about buying it.

Below are my 7 best takeaways from Thinking, Fast and Slow.

1. Your Brain Has Two Systems: System 1 (fast, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, analytical)

It’s a bizarre experience reading Thinking, Fast and Slow. Throughout the book, Kahneman asks you questions, knowing you will make a mistake while trying to answer them.

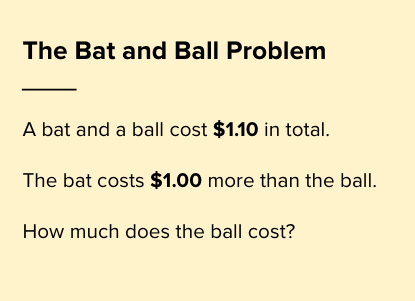

Here’s an example. Remember your immediate response as you read it.

If you’re like most people, you will have answered that the ball costs $0.10, which is incorrect (the answer is $0.05). What happened here?

System 1 — the fast, reptilian part of your brain that works on intuition — made a snap, “good enough” answer.

It was only when System 2 — the slow, analytical part of your brain — was activated that you could understand why $0.05 is the correct answer.

Did your brain trick you? Are you bad at math? No, this is your brain working exactly as it is supposed to, and the reason for that is due to this concept of Cognitive Ease.

2. Cognitive Ease: Your Brain Wants To Take The Path of Least Resistance

Your brain HATES using energy. It wants to be at peace, it wants to feel relaxed.

It likes things that are familiar, it likes things that are simple to understand. It is drawn to things that make it feel like it’s in a safe environment.

This is Cognitive Ease.

Thousands of years ago, if you were in a familiar environment, the odds of your survival were much higher than if you were venturing into a new, unexplored jungle.

Therefore, your brain prefers familiar things. It prefers things that are easy to see, and simple to understand.

This has huge implications particularly when it comes to persuasion, marketing, and influence, because this means that Cognitive Ease can be induced!

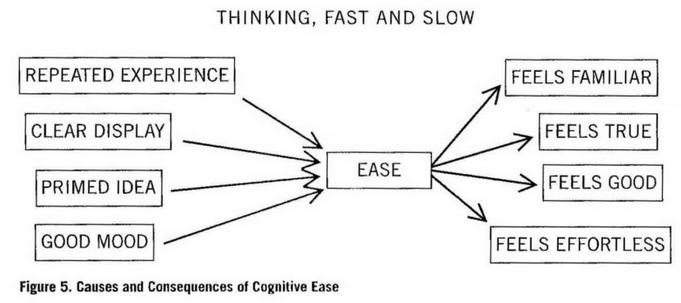

Here’s Kahneman’s take on how to that works:

Cognitive Ease is a major reason why brand advertising exists. It’s why companies spend so much money on celebrity endorsements, ad campaigns and jingles. We know that consumers are satisficers that take the path of least resistance.

It’s also important for UX teams and CROs. By inducing Cognitive Ease, they are better able to lead users down a designed path.

Cognitive Ease is interesting because it can be taken advantage of by bad actors. Look at the chart above. Nowhere in there does it specify that the inputs are accurate or factual.

Indeed, Kahneman alludes to this in the book:

A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.

Authoritarian institutions and marketers have always known this fact. But it was psychologists who discovered that you do not have to repeat the entire statement of a fact or idea to make it appear true.

3. Question Substitution: When Faced With a Difficult Question, We Answer a Cognitively-Easier One

I found the idea of question substitution fascinating, because after I read about it, I immediately caught myself doing it all the time.

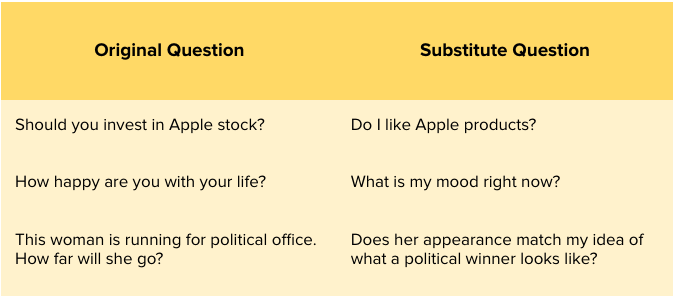

When we’re asked a question that is not Cognitively Easy, our brains immediately substitute the question to something that is easier to parse. Here are some examples:

The questions on the left require the activation of System 2. In order for you to provide a thoughtful answer that accurately represents your opinion, your brain will require time and energy.

For really important questions (performance reviews, immigration interviews) we are likely to consciously activate System 2. But for most things, we’ll instantaneously swap the difficult question for an easier one that System 1 can solve.

As a marketer, you should be wary of this any time you do customer interviews or run surveys.

4. WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is)

Imagine a friend who has grown up in a country that has a problem with aggressive stray dogs. Also imagine that friend has been chased by these dogs, and has several friends who have been bitten by such dogs.

Now even when you bring your friend to a home that has the friendliest, cuddliest dogs in the world, it’s likely that his System 1 will immediately go into freeze, flight or (hopefully not) fight.

What he’s seen is “dogs = terrifying” and it will be very difficult to convince him otherwise. What he’s seen is all there is.

Our brains can confidently form conclusions based on limited evidence. We readily form opinions based on very little information, and then are confident in those opinions.

WYSIATI is one of the reasons why modern politics is so polarizing.

People take the cognitively easy route of listening to others on “their side”, until eventually the only information you’re exposed to is the ones that confirm your existing beliefs.

From a marketer’s perspective, WYSIATI justifies things like branding or awareness campaigns. If your target audience is researching the problem you solve, and you’ve made sure that your brand keeps popping up in Facebook groups, industry conversations, Quora answers … then you’re in a great position.

5. Framing and Choice Architecture: Your Opinion Can Change Depending On How You’re Asked

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office.

The doctor writes on some papers. He types on his keyboard. He looks at you and says you need major surgery.

He takes a breath, and says:

“The chance of you dying within one month is 10%.”

Take a second to think about how you felt reading that sentence.

Now imagine he instead said this:

“The odds of survival one month after surgery are 90%.”

How did you feel after reading that one?

It’s the exact same stats, but phrased differently. Most people feel that the second one is more reassuring, despite being factually equivalent to the first.

Framing is completely where copywriters earn their salary. Being able to identify an alternate, more attractive framing can make the difference between a winning campaign or a flame-out.

Take the following example, which one do you think would sell better?

6. Base Rate Neglect: When Judging Likelihood, We Overvalue What “Feels” Right and Undervalue Statistics

Think of “base rates” as the frequency of some event occurring, based on historical and observable data.

It can be anything: maybe the “base rate” of rain during a Saturday is 8.5%. The base rate of medical students who are still doctors at age 40 is 10%. The base rate of coffee shops that close down in the first year is 94%.

Now, here’s the rub: for some reason, our brains tend to ignore base rates when we judge the likelihood of something.

Librarian or Farmer?

Here’s an example from the book, where Kahneman asks you to guess someone’s job based on some info:

“Steve is very shy and withdrawn…he has a need for order, structure and has a passion for detail.”

Is Steve more likely to be librarian or a farmer?

If you’re like most people, you will have intuited that he is a librarian, because of the description; while ignoring the reality of base rates. That is, there are far more farmers than librarians in the world. Based on the short description given, it “feels right” that Steve is a librarian, yet it is statistically likely that he is a farmer.

Here’s another example that hopefully makes it more clear:

“John is very athletic and plays sports. He is a strong advocate of LGBTQ rights and attends rallies and parades.”

Which one is more likely?

a) John is a basketball player.

b) John is a basketball player and is gay.

Hopefully you will have realized that there are more people in (a) than there are in (b). If your brain keeps telling you that the answer is (b), then it just proves the strength of Base Rate Neglect.

7. Sunk Costs: We Hate The Idea of “Wasting” What We’ve Already Put In

The Sunk Cost Fallacy is our tendency to follow through with an action — even when it no longer makes rational sense — because we are influenced by what we’ve already invested in it.

Imagine that your boss asks you to attend a 3-day marketing conference in a different country. You research the conference and get excited — speakers look good. Topics look interesting. You are enthusiastic to go.

Fast forward to Day 2 of the conference. Day 1 was a dud: the speakers were mediocre and networking has been a bust. Day 2 looks like more of the same.

Do you feel like you have to attend the rest of the conference?

Most people will say yes, because of the expense and time cost that has already been invested. You feel like you have to “get the most” out of what has been paid, and you feel additional pressure because of your boss.

And so you stay for the whole thing, ignoring the opportunity cost of your time — maybe you could’ve been working on other projects; perhaps you could’ve instead networked outside of the conference in that city; perhaps you could’ve done any other thing that would’ve been a better return on your time.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy is so deeply ingrained in our thinking that it has the ability to influence major company-wide decisions, and impacts things like resource allocation (imagine a marketing campaign that just isn’t working — let me just do another push!)

Read how to avoid the Sunk Cost Fallacy here.

Conclusion

As a marketer, your job fundamentally involves resource allocation and decision-making: where do you spend time and money? Which campaign deserves attention? What opportunities is everyone missing because of narrow framing?

Anything that helps you improve your decision making abilities & reduce unforced errors in thinking is usually a great use of time.

Thinking, Fast and Slow is one of the best books for marketers, but just prep yourself. It’s a dense read, which discourages many from getting the most value from the book. Skim freely and skip chapters liberally.

Read next: The Tragedy of Survivorship Bias (and how to avoid it)